This month’s reading picks from the Caribbean, with reviews of The Stranger Who Was Myself by Barbara Jenkins; A Scream in the Shadows by Mac Donald Dixon; Pleasantview by Celeste Mohammed; and Cane, Corn & Gully by Safiya Kamaria Kinshasa

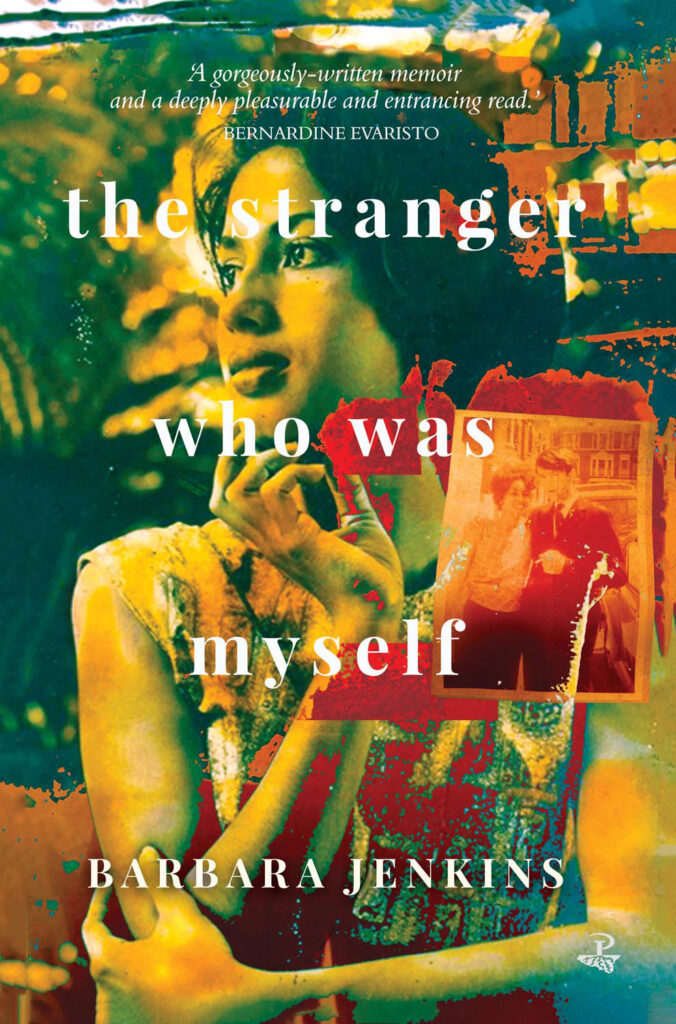

The Stranger Who Was Myself

by Barbara Jenkins (Peepal Tree Press, 278 pp, ISBN 9781845235345)

In Trinidadian novelist and short story writer Barbara Jenkins’ first full-length non-fiction offering, the past is held to account — specifically, her own past. The Stranger Who Was Myself, which takes its title from Derek Walcott’s poem “Love After Love”, does what so many memoirs purpose to do, yet few achieve: it tells the truth. Generously, honed with all the wit and insight that characterise her fiction, Jenkins lets us in — showing us her childhood and coming of age, tackling colourism’s scourges while interrogating memory’s labyrinthine vaults. This will be a nigh-impossible book to relinquish. Long after it’s read, images and impressions persist with the reader, transforming her indelibly. From the ascending verdure of Upper Belmont Valley Road to the windswept decks of Atlantic-crossing ships, every landscape in this history feels impossibly yet remarkably personal.

A Scream in the Shadows

by Mac Donald Dixon (Papillote Press, 200 pp, ISBN 9781838041533)

St Lucian author Mac Donald Dixon’s third novel brews a heady concoction of justice and redemption in the crime fiction genre. Determined to clear his Papa’s name for the murder of his older sister Laurette, a youth discovers that villagers and townsfolk are far more likely to dispense secretive whispers than offer helpful solutions. Superstitions — steeped in the patriarchal mores of the island — add fuel to rumours about Laurette’s violent end, and our protagonist struggles to separate illusion from concrete proof. A Scream in the Shadows takes on a moral responsibility to raze to the ground systemic failures of policing and judicial due process. That it does this without tendentious handwringing is to the author’s credit. The conflicts feel acute in their gravity, the suffering palpable, the road to emotional closure a hard-trod journey.

Pleasantview

by Celeste Mohammed (Ig Publishing, 208 pp, ISBN 9781632462022)

Winner of the 2022 OCM Bocas Prize for Caribbean Literature, Celeste Mohammed’s victory makes her the third woman from Trinidad & Tobago to claim the overall prize. The realities of the islands she presents are visionary, scathing in their intimations, brilliant in the intensity of their transmissions. This is an utterly identifiable landscape — hewn of major and minor corruptions, prison escapes, colourful adulteries, suppressed lesbian desires, Carnivalesque wining sessions. Wielding judicious narrative control, Mohammed teases the threads of Pleasantview’s interwoven stories into a deeply satisfying tangle. In a pivotal, wordless scene between a couple, one sees in the other’s eyes “love, shame, the truth he couldn’t say”. It’s a fitting microcosm for the subterranean experiences lurking in myriad interactions between the many bittersweet beloveds and sworn enemies we meet in these pages. This is irresistible writing, rippling with fierce assurance.

Cane, Corn & Gully

by Safiya Kamaria Kinshasa (Out-Spoken Press, 100 pp, ISBN 978-1739902124)

Every poem has at least one heartbeat. Nowhere is this more evident than in the remarkable debut collection of British-born, Barbadian-raised Safiya Kamaria Kinshasa. Cane, Corn & Gully employs Labanotation — an illustrative system depicting human movement — to summon and converse with the Afro-diasporan movements of Black Barbadian women throughout history. Reclaiming their stories from the fringes of the archives, Kinshasa’s poems move fluidly — with playfulness and formal experimentation, confronting superstructures of racism and neocolonialism. The poet’s diction doesn’t tiptoe through expected paces; it exults in kinesis, and generates startling significances from lyricism and daring inventiveness. Even the Barbadian canefields in “I Salted de Mud With My Palms but More ah Me Grew” offer their own stirring resistance: & dem tell me no, if you keep getting cut down / & keep growing yuh mussie mean something.