“Water, water everywhere / Nor any drop to drink.” The famous lines from Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1834) have entered into common parlance. They evoke the horror experienced by those becalmed or shipwrecked, surrounded by an infinity of salt water that, if drunk, will cause certain and rapid death.

It is widely understood that sea water, even consumed in small quantities, leads quickly to an overdose of salt, to dehydration and kidney failure. Popular fiction and films contain many examples of marooned mariners and shipwreck survivors in lifeboats driven mad by a raging thirst in the midst of a vast ocean.

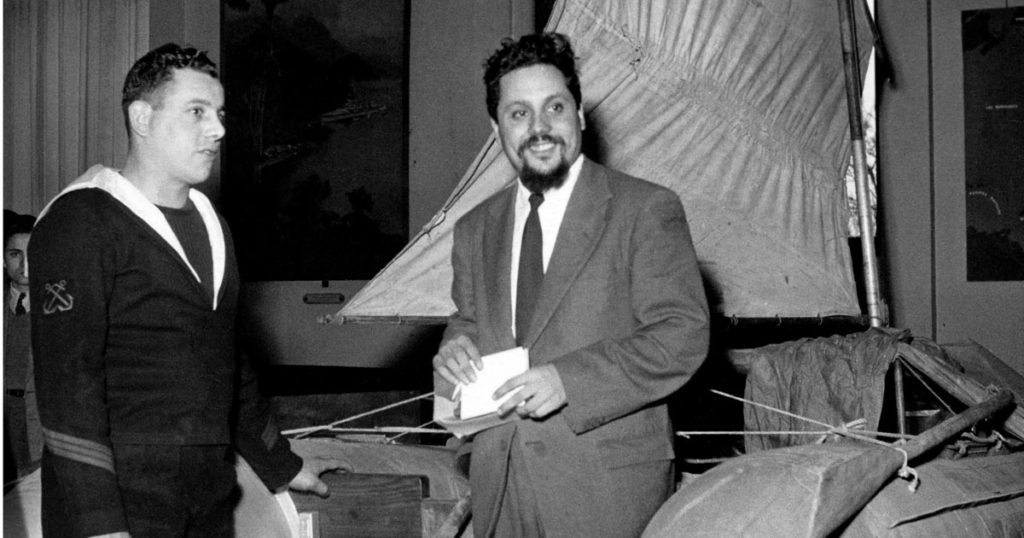

But some people are simply unwilling to accept mainstream thinking. One such maverick was a French doctor who rejoiced in the name of Alain Bombard. His determination to prove that humans can survive extended periods afloat in small vessels — without supplies of food and, most importantly, fresh water — led him on an extraordinary journey across the Atlantic 70 years ago, a journey that ended on a remote beach on the northwest coast of Barbados.

Bombard was not a daredevil adventurer in search of publicity, but a scientist with a theory to test. In a 15-foot rubber dinghy with a small triangular sail, equipped with the basic supplies that might be found on a lifeboat, he set off from Las Palmas in the Canary Islands on 19 October 1952, starting a 65-day crossing towards landfall in the Caribbean.

This was no idle experiment, but a research mission carried out because Bombard had an idea that he thought could save many lives. Born (1924) and educated in Paris, he had worked as a doctor in a hospital in the northern French port town of Boulogne-sur-Mer, and it was there that he saw first-hand the catastrophic nature of disasters at sea and the critical struggle for survival in their aftermath.

A shipwrecked trawler caused 43 deaths among Boulogne’s fishing community in early 1951, and it was reckoned that about 150 fishermen died in northern France each year — and perhaps 200,000 seafarers worldwide. Of these, it was estimated that at least a quarter perished in lifeboats from thirst, hunger and despair. The huge loss of life during the Second World War among sailors and civilians had brought the challenges and mortal dangers of the sea into sharp focus.

Dr Bombard’s theory was relatively simple: morale among castaways could be maintained by the prospect of survival, and the chance of survival could be improved by hydration and nutrition. The sea, he thought, could provide both.

Nutrition could be obtained by eating fish, easily caught with rudimentary equipment, and by consuming nutrient-rich plankton, scooped up in fine nets and swallowed by the spoonful. As for water, rain could be captured and stored, and — more interestingly — semi-filleted fish could be squeezed in a press to produce a liquid significantly less salty than the sea in which they live. He even thought that small amounts of sea water, if diluted with non-salty rainwater, would not cause serious damage to humans.

By 1952, Bombard was ready to test his hypothesis. A trial run from Monaco to Tangiers and then to Casablanca was successful — though a planned companion perhaps sensibly dropped out at this stage. Then in October, after a brief visit to Paris to view his new-born daughter, he set sail from Las Palmas, equipped with a sextant, a tarpaulin, some fishing equipment and — importantly — a sealed box of food and water. If the seal was found to be broken, the mission would be deemed a failure.

Bombard kept a diary of what happened next, later turning it into a successful early example of extreme travel writing. It was a “starving thirsty hell”, he wrote, detailing the nauseating diet of plankton and raw fish that sustained him. There was no rain for three weeks, he had little idea of where he was, and storms buffeted the tiny craft, snapping the mast and soaking the solitary mariner.

The “voluntary castaway”, as he styled himself, suffered multiple health issues — nausea, skin complaints, mild paranoia — and confronted alarming incidents as he was pushed along by irregular trade winds and erratic currents. Perhaps most disconcerting was the arrival of curious swordfish whose sharp bills might easily have punctured his rubber vessel, the aptly named L’Hérétique.

Bombard admits that he was close to despair when, on day 53, a ship appeared on the horizon. The Arakaka — a cargo ship en route to British Guiana from Liverpool — spotted him, came close, and from a loudhailer the captain informed him that he was still 600 miles from his projected destination. Demoralised, Bombard accepted an invitation to come aboard, have a shower, send a telegram to his wife and, unwisely, eat a small lunch of fried egg, liver and cabbage.

The effect on his fragile digestive system was to prove disastrous. Yet despite the dispiriting revelation of his position, Bombard resolved to continue and set sail once more. The Arakaka’s captain, impressed by the Frenchman’s courage, promised that he would have Bombard’s favourite piece by Bach played on the BBC Overseas Service on Christmas Day.

Re-energised by this fortuitous encounter, Dr Bombard sailed on, plagued by diarrhoea and still hoping to make landfall on the French territory of Martinique. The presence of seabirds and then the appearance of a Dutch cargo ship bound for Trinidad confirmed that the dinghy was nearing land. But now the objective changed to Barbados — still 70 miles away, but much closer than Martinique.

In his book The Bombard Story, he describes his elation at spotting a lighthouse beam flashing on clouds in the dark sky. Negotiating Barbados’ rocky northern coastline, he finally saw a beach and a group of fishermen who helped the emaciated mariner ashore and dragged the dinghy onto the beach.

Bombard insists in his record that the seal on his emergency supplies remained unbroken and that he distributed the tinned food to excited locals. Exhausted, he was led to the nearest police station where, with a French appreciation of colonial-era Britishness, he recalls:

The officer in charge was clearly at a loss to decide whether I was a pirate or an exceptionally foolhardy yachtsman, but with the splendid correctitude of the British policeman, who is at the same time father-confessor to those confided to his charge, he sat me down in front of a cup of tea and a piece of bread and butter.

It was Christmas Eve, and the next day — as promised — the BBC broadcast Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos, dedicated to the voluntary castaway. He had lost 55 pounds in weight and was anaemic but, as he wrote, “I proved conclusively that I could quench my thirst from fish and that the sea itself provides the liquid necessary to health.”

Bombard’s journey was widely reported, caused controversy (he was accused of using his supplies) and was, above all, highly successful because it encouraged unprecedented discussion of survival techniques at sea. The idea of squeezing fish for fresh water was considered eccentric, but some of his ideas — better equipment in lifeboats in particular — led to action that undoubtedly saved lives.

He enjoyed his celebrity status, was involved in further adventures, and in 1981 was appointed an environment minister in the French government — opposing what he saw as the cruel business of foie gras production. Whether he continued to consume teaspoons of plankton is not recorded, but he died aged 80 in 2005.