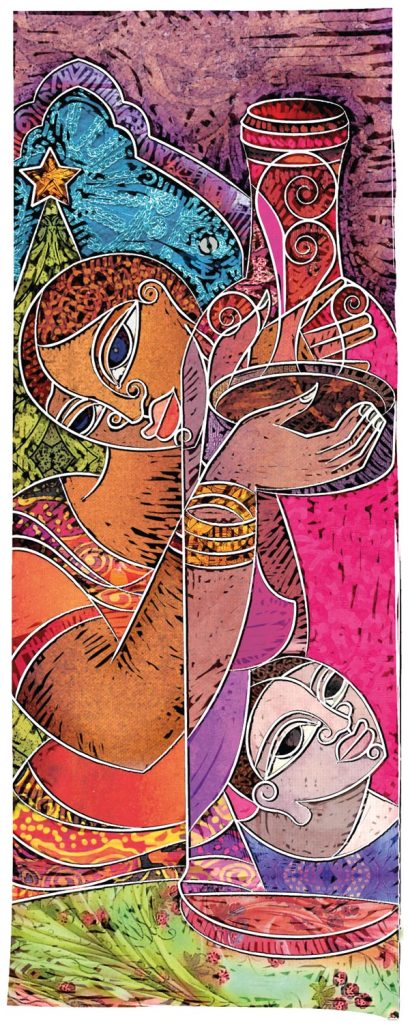

‘Twas the night before Christmas … but it wasn’t the Yuletide log burning in Donna Yawching’s house — it was her attempt at baking Christmas cake. Originally published in 2007, and reproduced in 2023

Christmas is coming, the goose is getting fat. Chestnuts roasting on an open fire. Visions of sugar plums danced in their heads. Why is it that so many Christmas images revolve around food? I swear it’s done on purpose, to make me feel inadequate.

I am not a cook—or at least, not a willing one. I love to eat, and my own childhood Christmases were indeed defined by food. In the Caribbean, Christmas is a culinary extravaganza. By October, the raisins and sultanas, currants and fruit peel, are soaking in rum and cherry brandy, preparing for their big moment as the world’s richest, booziest fruit cakes.

This is the epitome of Christmas, the test of whether or not you are a Good Caribbean Woman. All sins are forgivable if you can produce a good fruit cake. My mother, who was otherwise not a particularly enthusiastic cook (and yes, that is an understatement), made a damned good fruit cake when I was a child—actually, she still does. It was rich and dark, and so moist it was almost liquid; and you could get drunk just by standing next to it. It was archetypal.

A couple of weeks before Christmas, she would rummage in the back of the darkest kitchen cupboard, and emerge with the components of a grim metal implement that bore an uneasy resemblance to some sort of medieval torture instrument. This was the hand grinder; it would be assembled and screwed onto the edge of the kitchen table, the handle attached—and guess whose job it would be to stuff the monster with handfuls of sodden, alcoholic fruit, and force the stiff handle around and around? It wasn’t an easy task, and it seemed to go on for hours (no one ever makes just one fruit cake; you make half a dozen at least). But the end result was worth it.

Well, as noted above, I am a reluctant cook. I’ve spent most of my life avoiding kitchens; my single years were a blur of Cokes and danishes and Kraft cheese slices and spaghetti sauce (not necessarily all at the same meal). Nowadays, with two hungry sons to keep stoked, I’ve learned the essentials under duress, and so far we’re all still alive.

Some years ago, however, maternal guilt got the better of me. I felt I should be doing more to instil warm yuletide memories in my boys than merely buying them bicycles and computer games, and slinking off to various friends’ houses in search of Christmas fare. I decided to make a batch of fruit cakes.

I swear, I followed the recipe. I soaked the fruits for weeks. Not owning a grinder, I hacked away at them (not very successfully) with a hand blender; then decided that almost-intact raisins would be just as good as ground-up ones—chewier, you understand. I mixed and stirred and beat and folded, and finally I closed the oven on my efforts and collapsed.

What the recipe had not told me (no doubt assuming a reader of normal culinary intelligence) was to drain some of the liquid from the fruit before folding and stirring and mixing. When my cakes should have been cooked, they were in fact burning on the outside—and liquid inside.

By this time it was getting rather late, and I was throwing a party the next night. None of my friends, luckily, expects haute cuisine from me; but I had been hoping to impress them with my cakes. That was now obviously a non-starter; but I thought I might still be able to salvage something for the boys, if I left the cakes to dry out in the oven overnight. I switched off the oven and went to bed.

I woke with a start some hours later—was that my name being called? Impossible—it was after midnight. No, there it was again. It was my neighbour, shouting frantically: “Donna, there’s smoke coming out of your house!” I leapt up, and indeed there was. My whole house was enveloped in a mushroom cloud; I could hardly find the kitchen—where, as it turned out, my oven was not quite off, and my cakes were on fire. Without my vigilant neighbour, we would have been too.

The rest is a blur, and the short version is that my house didn’t burn down, though it could easily have. The firemen—whose station was two minutes’ drive away—turned up 45 minutes later, well after I had extinguished the blaze with a pot or two of water. They had gone to the wrong area altogether.

The next night, when my guests arrived, only the faintest whiff of carbon lingered in the air, cunningly disguised by the aroma of vanilla oil. And

I had learned two valuable lessons:

1 The true meaning of Christmas thankfulness, and

2 If I want a cake, I’ll buy it.

Clearly, I am not cut out for tradition. And for what it’s worth, my sons have a Christmas memory they’ll never forget.