One of the unexpected pluses of televised international sport is the opportunity it gives to appreciate the world’s many national anthems. These always take place before the action starts, but they’re sometimes more entertaining than what follows.

Everyone probably has a favourite. I like (or used to like) Russia’s solemn state anthem — composed in 1944 but with words much modified since — while my wife favours the stirring sound of France’s “La Marseillaise”, even though its sentiments are unashamedly revolutionary and bellicose.

It’s fun to watch the sportspeople react to their national song: some join in enthusiastically, while others, maybe tone deaf, mime sheepishly or remain tight-lipped.

The significance of the pre-sport ritual struck me last July when England’s football team played Haiti in the Women’s World Cup in Australia. England won 1–0 due to a dubious retaken penalty and despite a brilliant performance by Melchie Dumornay. But for me the anthem competition was indisputably won by the side who were narrowly beaten on the pitch.

The English women were seemingly enthusiastic that an unelected elderly man might long reign over them, but the Haitians had an anthem that spoke of their land, of past sacrifices and the common people:

Let us be the only masters of the soil.

Let us march united, let us march united

For the Country, for the Ancestors.

Hereditary monarchy is routinely celebrated in “God Save the King”, but Haiti’s anthem tells a very different story. It was first officially played some 120 years ago at an event commemorating something that had happened 100 years earlier and which is a key moment in Caribbean history: the birth of a free and independent Haiti.

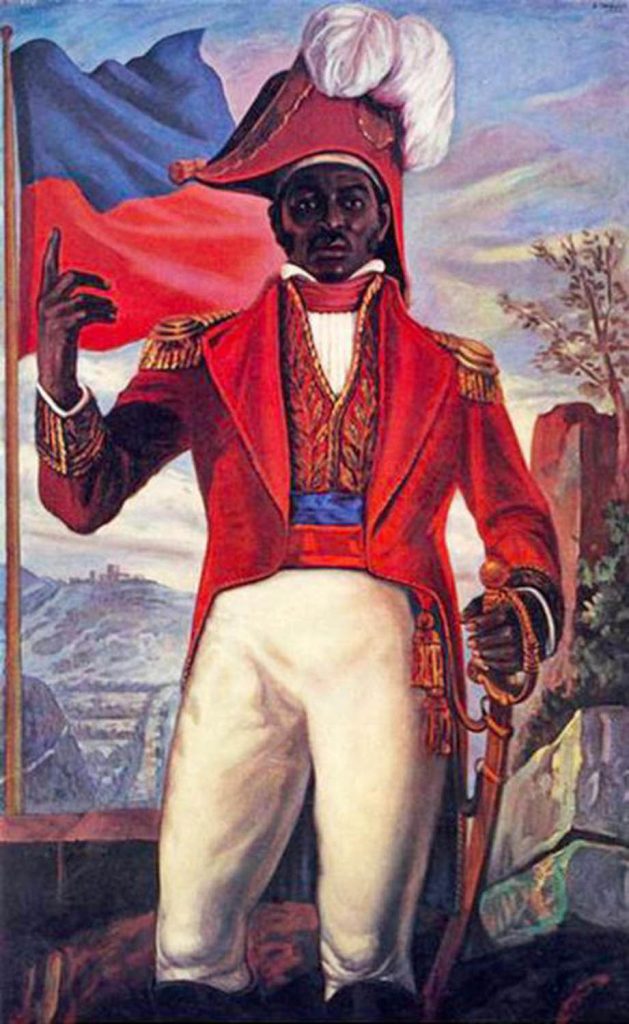

Named “La Dessalinienne”, the anthem was composed to mark a century of Haiti’s existence, and its name pays homage to a man who is often seen as the father of the nation.

On 1 January 1804, General Jean-Jacques Dessalines — a former slave and battle-hardened freedom fighter — was centre stage in the coastal town of Gonaïves for the public reading of the declaration of independence. After 15 years of revolution and war, the French colony of Saint-Domingue — once the wealthiest in the world — was no more.

The new state of Haiti, its name recalling its pre-colonial past, had come into being. It was born in ruins — the plantations and many towns burnt and looted, the slave owners and Napoleonic army driven out or killed. Everything was to be rebuilt, and the threat of reinvasion from France and other colonial powers remained very real.

Dessalines was illiterate and spoke no French, but the declaration was written in the language of the defeated colonists and was written and read out by his secretary Boisrond-Tonnerre after Dessalines had briefly addressed the assembled crowd of soldiers and townspeople in Kreyòl.

It was uncompromising in its hatred of the French and their legacy:

Begin with the French! Let them tremble upon approaching our coasts, if not because of the memory of the cruelties they carried out here, at least from the terrible resolution we are going to take to punish with death whatever born Frenchman soils our land of liberty with his sacrilegious step.

Rallying the new citizens of Haiti with a rhetoric of revenge and militant nationalism, the declaration was a foretaste of the violence and turbulence that ensued. Dessalines himself was assassinated in October 1806, and Haiti endured decades of civil war and foreign intervention.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, a national anthem was not a priority for the beleaguered founders of Haiti, and it would take a century for the shattered country to adopt a musical expression of its identity.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, a national anthem was not a priority for the beleaguered founders of Haiti, and it would take a century for the shattered country to adopt a musical expression of its identity

The centenary of independence offered a context for national pride, and President Nord Alexis — who had come to power in December 1902 through a series of plots and uprisings — was keen to stress continuity and his own legitimacy. As part of the centennial, a National Association was convened to organise celebratory activities, and these included a competition to compose and write a national anthem.

Thanks to Rebecca Dirksen’s research, we know that the competition involved two separate stages: first, in June 1903, entrants submitted lyrics to be judged by a five-strong jury. Then composers were invited to offer musical scores, to be judged by another committee.

The winners were the poet Justin Lhérisson and the composer Nicolas Fenélon Geffrard, who wrote a piece with what Dirksen describes as “crisp dotted rhythms, brisk tempo, and melody solidly built around arpeggiated chords”.

The end result, deemed suitably patriotic, satisfied the organisers, one of whom (a historian) suggested that the anthem’s title should honour Dessalines — though the revered leader did not feature in its lyrics.

There are conflicting accounts of when “La Dessalinienne” was first performed in public, but it is generally agreed that it was officially premiered on 1 January 1904 in the capital Port-au-Prince. According to Professor Dirksen:

[C]rowds numbering in the thousands were guided through singing the words and melody during the Independence Day celebration. On that day, “The Dessalinienne” accompanied the renaming of an important public square to the Place des Héros de l’Indépendance and the inauguration of monuments that would soon be built to honour the nation’s revolutionary figures …

In 1919, the piece was formally adopted as Haiti’s hymne national by the National Assembly, despite the fact that the country had been under United States occupation since July 1915, and it was duly performed at a ceremony marking the withdrawal of American forces in August 1934.

Ever since, it has been sung at official events and in Haiti’s schools, even during the long dictatorship of François “Papa Doc” Duvalier, who had a tendency to rename everything after himself.

As for the anthem’s creators, the composer Geffrar — a nephew of the president of the same name (1859–67) — lived mostly in Europe, was a professor of music, and died in 1930. His collaborator, Justin Lhérisson, died in November 1907 at the age of only 30. In his short life, he was a journalist, poet, and author of two novels that are considered important in the formation of a Haitian literary tradition.

Curiously, it was not until the 1980s that a version of the anthem in Kreyòl, the language of the majority in Haiti, was recorded by Ansy Dérose. Since then, various versions have appeared online, and the Kreyòl lyrics are often sung alongside the French words in schools.

It was in Kreyòl that the Haitian women footballers and their fans sang before their match against England in Brisbane. But officially, in a state and diplomatic context, the anthem’s words remain stubbornly French — a situation that the unforgiving Dessalines would certainly frown upon.