Connoisseurs of fine cigars may well disagree, but many these days think that tobacco has a lot to answer for — chiefly countless premature deaths and ill-gotten profits. The “witching weed” has also played a not always benign part in various historical events, and one of these was the founding of the first ever English colonial settlement in the Caribbean islands.

As often happens, a key moment in history was brought about by a coincidence of personalities, circumstances and sheer chance — and in this instance, the moment occurred exactly 400 years ago on the beautiful island of St Kitts.

The events that followed encapsulate a great deal of Caribbean colonial history — conquest, war, inter-European rivalry, slavery and resistance. But what adds extra interest to the early days of St Kitts is the family at the centre of the story and a deadly dispute between half-brothers.

It all started with an Englishman named Thomas Warner, born in 1580 into a landowning family in Suffolk, England, and then a captain in the guards of King James I.

Warner seems to have been drawn to the idea of adventures in the “New World”, and in 1620 he accompanied Roger North — a veteran of Sir Walter Raleigh’s expeditions to South America — to the fledgling colony of Oyapoc, in an area of present-day Guyana that was largely Dutch-controlled.

The plan was to cultivate tobacco, which was already booming as a commodity in Europe a century or so after the first adventurers had brought it back across the Atlantic.

It was in Guyana that Warner encountered a Captain Tomas Painton, who suggested that one of the small Caribbean islands would make a better tobacco-growing base than the unstable mainland colony, which was abandoned soon afterwards.

St Christopher (or, more commonly, St Kitts), sighted and named San Cristobal by Christopher Columbus in 1494, had not since been settled and was ideal agricultural land, said Painton, with abundant water. Its Indigenous name Liamuiga means “fertile island”.

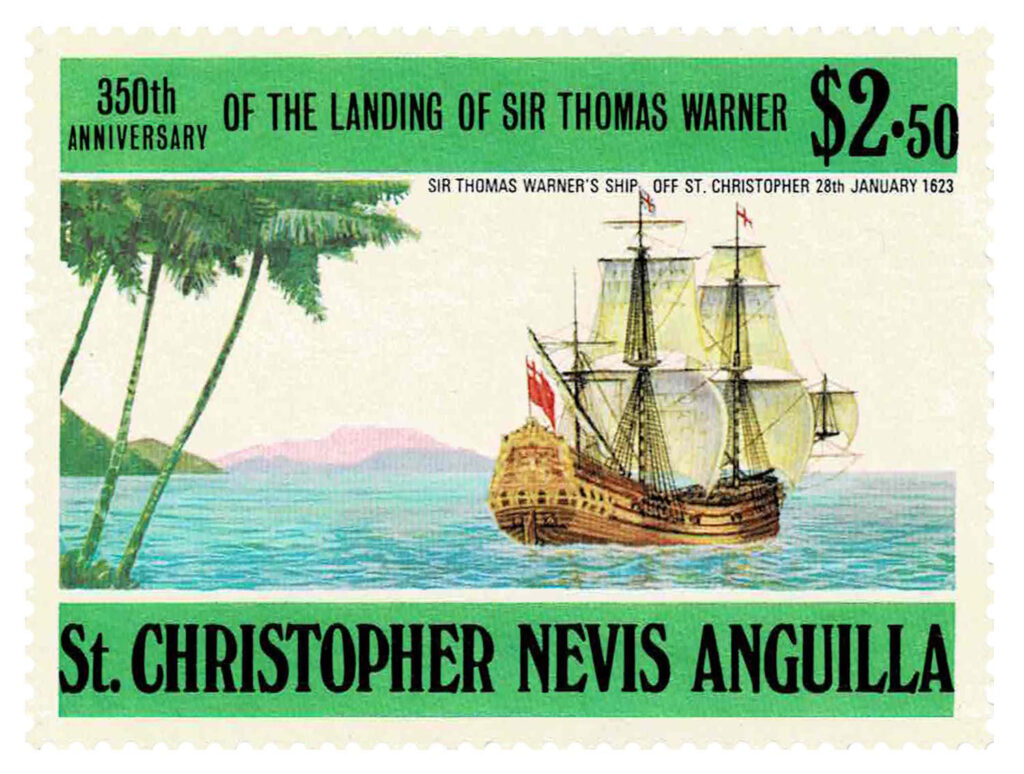

Sometime in 1623 — the records are sketchy — Warner set sail northwards through the archipelago until he reached the west coast of the island, at a place now known as Old Road Town. There his small group established a basic settlement and made contact with the Kalinago, or Carib, chief Tegramund, who seemed friendly.

Warner’s first priority was to seek investment and reinforcements, and almost at once he sailed back to England to attract money and men for his planned colony. By January 1624, he was back on the island with family, settlers, supplies and some interested merchants, and the first permanent English colony was established at Old Road.

From its beginnings, the settlement faced adversity. The first tobacco crop was destroyed by a hurricane. Then French colonists arrived on the island, demanding their own territory, and Warner was forced to agree a treaty dividing the fertile land.

Worse followed when Tegramund, understandably alarmed at the foreign invaders’ activities, planned an attack. The plot was betrayed and the English and French combined forces to massacre the Indigenous population — an event commemorated by a headland called Bloody Point.

Warner’s colony, though plagued by constant conflict with the French and the Spanish (who briefly invaded in 1629) was considered a success in England. He was knighted, and made Governor of St Kitts and Lieutenant General of “the Caribee Islands”.

The number of settlers grew so rapidly that Warner sent colonists to Nevis, Antigua and Montserrat to establish new settlements. The influx of new arrivals continued to be a problem, as there was insufficient land, and unrest grew among those who had been promised a fortune in the Caribbean.

Protests were violently put down by Governor Warner, who at the same time introduced slavery to the island, importing thousands of Africans to work on tobacco and labour-intensive sugar plantations.

By the time of his death in March 1649, Sir Thomas Warner was a powerful and wealthy man, worth the equivalent today of £100 million. His legacy was formidable: he had created the first viable English colony in the Caribbean and had navigated 35 years of war and political scheming.

He had also instigated some of the worst aspects of colonial rule, which were to spread across the region: the destruction of Indigenous culture, the imposition of slavery, and the creation of a plantation economy.

His tomb can be seen at St Thomas Anglican Church in Middle Island, not far from where he first set foot on St Kitts, and his name lives on most conspicuously in the Warner Park Sporting Complex in the capital, Basseterre. Its origins date back to 1923, when the colonial authorities decided to commemorate the 300th anniversary of the English arrival with a public park.

But the Warner family’s influence persisted in other ways, not least in a strange and tragic rivalry between two of Sir Thomas’ sons. Sir Thomas was married three times and had a daughter and three sons within these marriages.

Edward was born in 1609 and became the first Governor of Antigua in 1632; Thomas died in 1679 and not much is known about him; and Philip was born in 1612 and was appointed Governor of Antigua, 40 years after his brother Edward, in 1672.

And then there was a fourth son, confusingly also named Thomas, but better known as “Indian” Warner. He had been born out of wedlock in 1630 to a Kalinago woman, apparently from Dominica, and was brought up within the Warner family. When his father died, he faced ostracism as the illegitimate sibling, was treated as a slave, and fled St Kitts to Dominica.

How Indian Warner “escaped to his Carib countrymen in Dominica” (Dictionary of National Biography) is unclear, but he was apparently made welcome in an island where the Kalinago people were still dominant. Rising to a position of leadership, he cleverly took advantage of English-French rivalry and led expeditions against both colonial contenders.

The English described him as “chief Indian governor” of Dominica, and an uneasy truce existed until in 1674 when a force left Antigua, determined to put an end to the raiding parties and kidnappings allegedly carried out by Kalinago from Dominica. The 100-strong party was led by Governor Philip Warner, half-brother of Indian Warner.

The Antiguan colonists at first joined forces with Indian Warner’s community against an enemy Kalinago group and slaughtered them. Then, according to the distinguished writer Marina Warner, a descendant of Sir Thomas Warner:

“The two brothers met on board ship — Philip’s — under a flag of truce, but “Indian” and all those with him died in the subsequent conflict, some witnesses claiming they had been intoxicated on purpose by Philip and then murdered in cold blood.”

Legend has it that Philip, in an act of fratricide, sought out and killed his brother.

It was a Caribbean Cain and Abel drama. But, unlike his biblical counterpart, Philip Warner escaped punishment and lived on until 1689. The Kalinago would face further bloodshed, while St Kitts would abandon tobacco for sugar, and sugar for tourism.